Why LCA is Essential for EPR Compliance in Packaging

In the last few decades, virtually all industries, including the packaging industry, have adopted more sustainable products and processes—both by voluntary measures encouraged by consumers and data and measures enforced by mandatory laws and regulations.

With this adoption of sustainability, it seems that new acronyms emerge weekly, from LCA to CSRD to DRS to EPR, etc. In this article, we will give more insight into life cycle assessments (LCA) for packaging and how they can be an effective tool to ensure compliance with extended producer responsibility (EPR) laws for packaging.

What is a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)?

The first acronym we will uncover is LCA, which stands for life cycle assessment (also known as life cycle analysis). A life cycle assessment is a systematic and data-driven approach to calculate and analyze the environmental impacts of a product or service throughout its lifecycle—from raw material extraction to end-of-life. LCAs allow companies to identify environmental hotspots, report and make environmental claims effectively, and compare alternative materials, processes, suppliers, and more.

Life cycle assessments can contain many forms, often guided by different standards. One of the most widely used life cycle assessment standards is ISO 14040 and ISO 14044. ISO 14040 and 14044 set the framework to conduct a life cycle assessment, breaking the process into four distinct phases:

Define Goal and Scope

Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

Interpretation

The LCA process is complex and involves defining a functional unit, mapping a product system, collecting large amounts of environmental data from suppliers, and applying a rigorous analysis. We highly recommend exploring the ISO standards linked above along with our online courses to learn more about the robust LCA process. For the sake of this article, we will provide a brief overview of the LCA process, following the ISO 14040 framework.

1. Define Goal and Scope

An LCA starts by defining the goal and scope. The goal of an LCA is the purpose for conducting your LCA, for example, comparing the impact of different packaging materials or for reporting data to stakeholders.

The scope of an LCA involves defining the unit to measure your product (package) or service (functional unit) and mapping the product system (a flow chart of all the processes involved in creating your product or service and other outputs). The scope stage also involves selecting a life cycle assessment model (based on system boundaries)—common life cycle assessment models include cradle-to-gate and cradle-to-grave.

A cradle-to-gate LCA assesses the environmental impact of a product or service from raw material extraction (cradle) to the moment the product leaves the factory gate (gate)—this model does not include transportation to the consumer, consumer use, and end-of-life. On the other hand, a cradle-to-grave LCA assesses the environmental impact of a product or services from raw material extraction (cradle) to disposal at the end of the product's life (grave).

Another component of this stage is selecting the LCIA methodology that will include impact categories evaluated and calculation parameters; for the sake of this article we will focus on introductory topics.

2. Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

The LCI phase involves taking your mapped product system from the first stage and making a list of the interactions between this system and the environment. This data comes in the form of foreground and background data.

Foreground data is data that relates to the technical aspects of the product system. For example, how many grams of corrugated board is used in the production of an individual package.

Background data is data that describes the environmental impact of the product system. For example, the global warming potential and eutrophication potential of x grams of corrugated board. This data can come from direct supplier data or life cycle inventory (LCI) databases like Ecoinvent.

Once all relevant data is collected, the team conducting the LCA will then enter the data into LCA software to connect the background and foreground data in the product system, preparing to conduct the assessment in the next stage.

3. Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

The LCIA phase is the stage where the defined product system will finally be assessed, after turning LCI data into impact categories for calculation.

Impact categories help make sense of the often hundreds to thousands of lines of data contained in an LCI, consolidating them into a handful of impacts for further calculation. For example, in many LCAs, the impact category “global warming potential” is used to translate all emissions related to a product system (CO2, CH4, SO2, etc.) into one common unit (typically kg CO2e) to understand the total global warming impact of the climate system.

Forming impact categories in an LCA will often be defined by the life cycle impact assessment (LCIA) method the research team chooses, which is typically determined by the standard selected in stage one.

4. Interpretation and Analysis

The final stage of an ISO 14040 compliant LCA is a critical interpretation and review of the first three steps. It is important to note that best practices include critically reviewing your LCA throughout; don’t just wait until stage four to be critical of your process.

This stage involves investigating a number of questions related to the goal and scope, running sensitivity and contribution analyses, creating an LCA Background Report, and more.

Using a life cycle assessment to measure the environmental impacts of your packaging solutions is a data-driven and effective way to understand the life cycle of your package throughout the value chain, allowing one to identify hotspots, areas for innovation and improvement, and evaluate alternatives—all of which are essential to stay compliant with extended producer responsibility (EPR) laws enacted in a number of US states and about 30% of the countries in the world.

What is Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR)?

Extended producer responsibility (EPR) refers to a legislative approach where the producers of packaging (and other identified products / materials) in a defined territory are made responsible for funding and managing the waste management and externalities associated with their packaging, typically through membership and fees paid to a producer responsibility organization (PRO).

While EPR is relatively new to the United States, with laws passed in California, Maine, Oregon, Colorado and Minnesota, the concept is decades old—dating back to the 1990s with Germany.

The map below highlights which states in the United States have active EPR laws, EPR study bills, or EPR bills introduced that have not yet passed. The non-colored states are those that, from our research, do not have any current action on EPR for packaging.

.png)

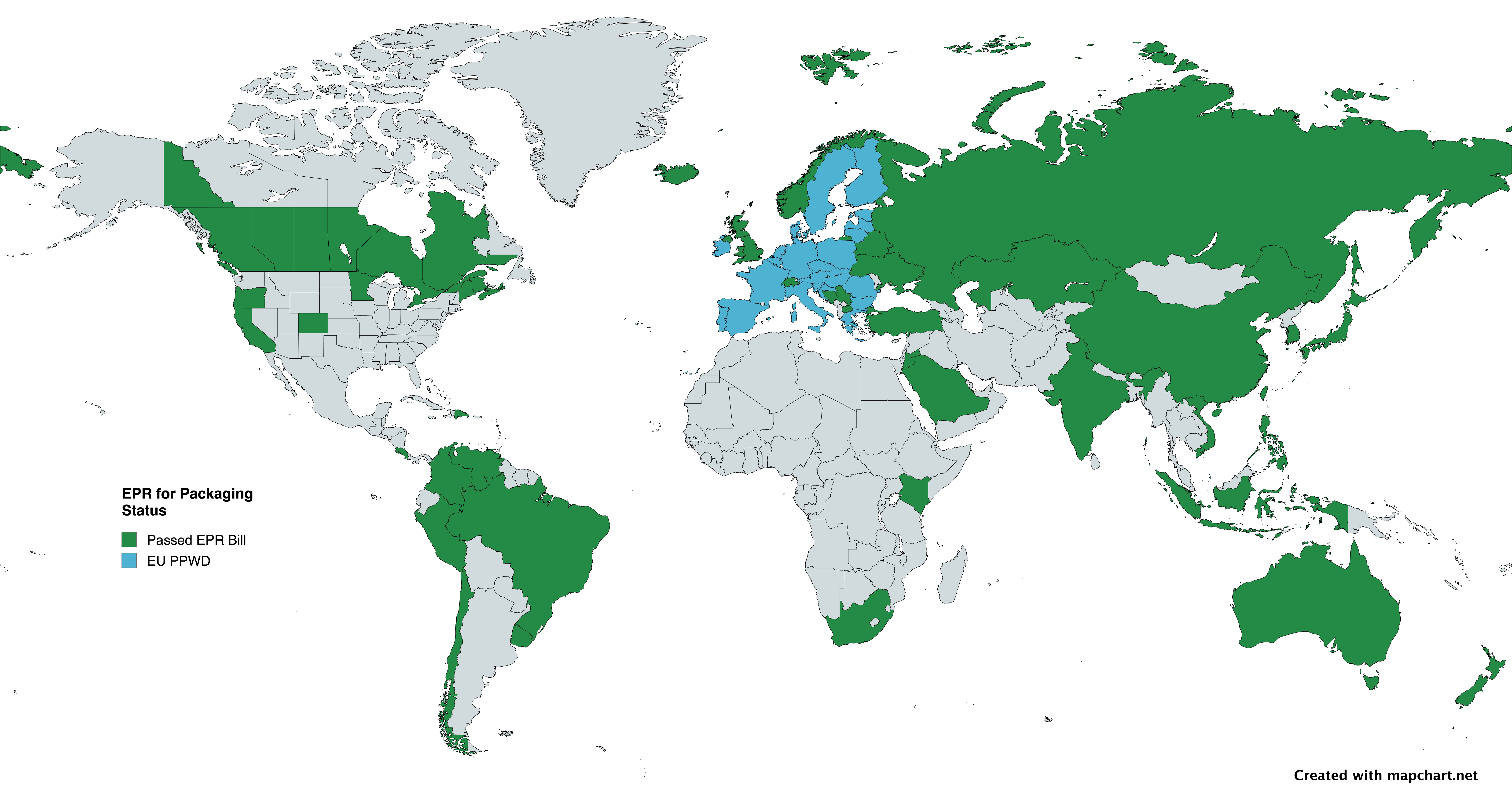

Over the past eight months, the team here at Packaging School has researched EPR for packaging bills from around the world—identifying over 60 nations that have established EPR for packaging programs in some form.

The map below shows how widespread EPR for packaging legislation has become since its origins in Germany. This map only highlights passed EPR bills, excluding study bills and introduced bills (see US map above). Countries in blue have EPR programs that are aligned with the European Union's Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive (PPWD).

Similar to the US map above, countries and territories in gray were found to not have action on EPR for packaging from our research—we understand research around this topic is dense and quickly developing . . . if we missed your state, country, or territory, please reach out at marketing@packagingschool.com

Through analyzing 60+ EPR programs that include packaging and packaging-related materials in their scopes, a few common themes emerged:

The use of producer responsibility organizations (PROs) for organization, management, and fee collection of programs. Some nations / states opt for single PROs and other multiple competing PROs. Many programs also allow producers to not join a PRO and handle EPR requirements on their own.

Many programs cite challenges with data availability around collection, reuse, recycling, etc.

A large percentage of programs have 5–10 year implementation timelines, with different milestones in which producers must register with a PRO, regulated materials are announced, reporting structures released, etc.

It seems that many programs, if not all, calculate fees based on the amount of tons per material introduced onto a market.

Some programs, like those aligned with the EUs PPWD, include targets for deposit return systems and other circular economy initiatives.

As you can gather from this brief overview, EPR for a program is an increasingly relevant and complex topic in the world of packaging compliance—making it mandatory for producers of packaging to understand and improve the sustainability and end-of-life collectability of their packaging throughout its entire lifecycle.

It can be daunting to get started in your compliance journey for EPR for packaging, but a good start is having a firm grasp of and mapping the environmental impact of your packaging systems throughout their value chains—a feat which can be achieved with the use of life cycle assessment methodologies.

The Link between LCAs and EPR for Packaging Compliance

An often overlooked tool when it comes to EPR for packaging compliance is the use of life cycle assessments to develop a deeper understanding of a package’s impact throughout its life cycle and to indicate opportunities where improvements can be made to align with EPR requirements.

Extended producer responsibility programs for packaging often require producers to have a deep understanding of the environmental impact of their packaging systems, including where externalities are generated throughout their value chain. From cradle to grave, producers are responsible for funding the collection and processing of their packaging waste, phasing out materials their territory views as problematic and reporting on their progress annually or biannually.

Conducting life cycle assessments on your packaging systems can assist in this process in a number of ways. Let’s look at a few.

Understanding Supply Chain and Impact Hotspots

As we explored above, life cycle assessments help map the environmental impacts of your defined product or package throughout its entire life cycle—from raw material extraction (cradle) to end-of-life (grave).

By understanding your package’s full environmental impact in different life cycle phases (raw material extraction, manufacturing, transportation, etc.), an organization can identify impact hotspots and areas to focus on and improve for EPR compliance. For example, through analyzing the LCA results of two different manufacturing processes, a packaging producer could unveil that an alternative process reduces the total global warming potential (GWP) and ozone depletion potential (ODP) by over 50%. Or, an organization could identify that a bulk of the packaging system’s environmental impact comes through transportation, allowing the team to set sustainability targets related to transportation and explore innovative transportation methods to invest in.

As previously noted, part of an LCA is mapping the product system in the goal and scope phase—this is where the producer will create a flow chart of the technical and environmental aspects of the packaging system. Exercises like these help visualize the elementary flows involved in a packaging system and understand the system at a deeper technical level.

Understanding a package’s value chain through LCA can be an effective tool to find areas to focus on and improve to ensure EPR compliance.

Sustainable Design and Research & Development

Once you have used an LCA to identify hotspots and develop a deep understanding of your value chain from a technical and sustainability perspective, LCA can help guide sustainable packaging design and R&D initiatives.

A large majority of EPR programs include provisions that phase out “less sustainable” and “problematic” materials (EPS, etc.), include extra fees for the use of less environmentally friendly materials, and incentivize the use of sustainable alternatives to packaging materials. Through running a comparative LCA comparing different packaging materials for the same package as the functional unit, a producer can unlock profound insights about the environmental impact of different material alternatives.

It is important to note that these analyses often uncover and involve navigating environmental trade-offs of different material types. For example, dunnage made of recycled paper might be found to have a lower global warming potential but a higher water footprint and eutrophication potential. In contrast, plastic air pillows might have a higher global warming potential and ecotoxicity, but they are lightweight, cause fewer transportation-related emissions, and have a smaller water footprint.

Furthermore, running life cycle assessments on emerging and alternative materials (bioplastics, etc.) can be useful in the packaging R&D process. Many EPR programs include incentivization structures to encourage the use of packaging systems with high amounts of recycled content or those that are compostable; use comparative LCAs to see which materials are fit for your packaging application.

With the use of LCAs, packaging professionals can effectively identify and navigate the trade-offs of using different packaging materials and explore the impact of emerging materials to help them stay compliant and ahead of current and emerging EPR mandates.

Sustainability & EPR Reporting

If you have been following the corporate sustainability realm for the last 5+ years, you will be well aware that voluntary and mandatory reporting frameworks are emerging all the time. From SASB to the CSRD and TNFD, conducting LCAs can help assist in the reporting process by providing packaging teams with comprehensive and comparable data about the environmental impact of a package through the lens of multiple impact categories.

As mentioned earlier, almost all of the EPR for packaging programs studied have reporting requirements, often either annual or biannual reports submitted to their PRO (or submitted themselves), which is then passed to the territory organization in charge of the EPR program (usually Department / Ministry of the Environment). The requirements for the contents of these reports vary by program but many contain themes including:

Quantity of different packaging materials placed on the market in the territory

Recycling and recovery rates for different packaging materials

Information on fees paid to PRO

Targets and Progress

Challenges / Obstacles, etc.

As you might imagine, an LCA can be an effective way to gather and contextualize some of this data and help create a snapshot of a packaging system's environmental impact allowing for goal and target setting. LCAs again prove to be an effective mechanism to stay compliant with EPR for packaging laws, especially through the lens of mandatory reporting under the programs.

Learn More About Sustainable Packaging and LCAs

As we have demonstrated, the world of sustainable packaging can get complicated rather quickly—especially with the rise in new mandatory EPR programs. Allow us to guide you through your sustainable packaging journey and teach you how to conduct packaging-related LCAs in our online 40-hour asynchronous program, the Certificate of Sustainable Packaging (CSP).

Our CSP program will guide you through:

Defining the key terminology needed to speak the language of sustainability with colleagues, customers, and other stakeholders

Constructing UN SDG-based sustainability targets and goals

Developing sustainable system designs (on material level)

Measuring the carbon footprint of your packaging

Selecting relevant offset programs to achieve carbon neutrality at the package level

Assessing the environmental performance of a provided package with an ISO 14040 compliant life cycle assessment software

Upgrade your sustainable packaging IQ today here!

By signing up you indicate you have read and agree to our Terms of Use. Packaging School will always respect your privacy.